I was born in Rome, from that kind of Neapolitan parents who are always ready to remember the excellences of their origin in a somewhat unreasonable way, based on nostalgia, as if they had made a mistake in emigrating from a colourful and multifaceted world to that mediocre stuff that they found in a city as insignificant as Rome. I am Roman: I speak with the accent of Rome, I have spent half a century exploring its alleys, women, churches, conferences, government institutions, careers, theatres, mad people, suburbs, political circles, the sultry nights, the days of winter, the nicknames, the ruins, the wealth of the popes, the fascist marbles, the cafés, the rivers, the bike rides and the rude and warm disenchantment. But I spent a lifetime dreaming of the South, as if I had only read Annamaria Ortese in my whole lifetime, even if at first I didn’t really know what the “South” was.

Then I realized that I was looking for a lost continent. A continent submerged by a geography which, by redesigning itself, had covered it with a new geopolitics just as water had covered Atlantis. The Eastern Mediterranean has ceased to be represented, overwhelmed in the transition from humanism to utilitarianism. The value of things has ceased to be a philosophical quality and has become a price.

Yet, in my formation, I have always felt something more than a taste in the granite that I could eat in the street-river of Modica, much more than some simple astronomy in the dawns in the east side of Puglia, much more than craftsmanship in the patience of a Calabrian fisherman who repairs the nets. I heard and saw the story of those merchants who left Etna carrying, so to speak, a load of lemons, landed in Lebanon to exchange them for pepper or metals, bypassed religious and linguistic differences, perhaps returning home with a wife who spoke in a strange way, but she knew how to love, make honey and build small wooden jewels. The Mediterranean has never been a division but a path that unites, it feeds a dispersive and self-raising cultural mixture with the richness of differences, produces art. Art, in Greek, is called τέχνη (tehni), art that the barbarians who arrived from the north were able to organize into technology, but which they never knew how to reinvent.

In Cyprus I have found that humanism I had in the confused dreams of a lifetime. In Cyprus I have found the Mediterranean. No, don’t say it’s like Sicily or Greece. The new continent, the Europe, has transformed its South into its own garden, building walls that did not exist before, at its South and East. The old continent, the Mediterranean, remained only in Cyprus.

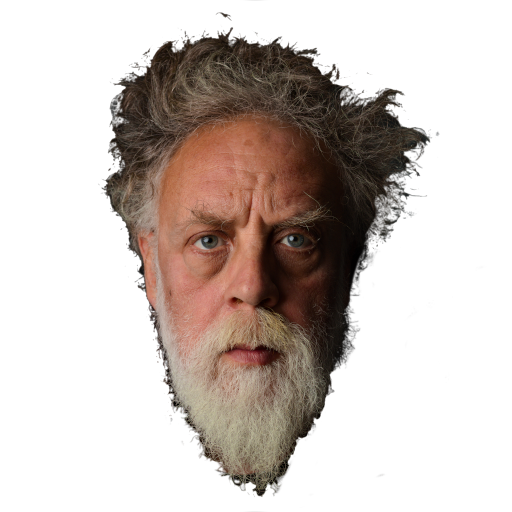

I sold the house and gave up everything: the safe job, the professionalism related to an extraneous model, the old and recent friends, the wines, the Italian beauties and the complications of living according to a furious scheme, the nervous humanity of our cities, the lost young people, a motorbike and two cats (which I still have to place somewhere). Convinced to open a bistro — without knowing how to do it — I landed here and started taking photos, almost without realising it. I came from a world where the reaction to the attention of a lens is «oh hell, are you a cop?» or «please no, I’m ashamed». In the middle of the Mediterranean, I found endless «thank you», because if I observe you I like you, I like what you are doing, I am giving you my attention, I am going to tell your story. Because the priceless has a value.

The first that I have I found, in Cyprus, is a mixture of languages and faces: Greek and Turkish, both in the declination of very pronounced dialects, English, because a hundred years of colonialism has a weigh, but also Armenian and Arabic and French and Italian, because history is history, up to the infinite languages of migrants, who are so many in Cyprus.

And I have found art, understood not as the grandiose excellence of cathedrals (which also are in Cyprus) whose body is a monolith celebrating power, but as the identity fabric of a people that gathers not around a language or a religion, but around what it creates. Art, in Cyprus, is a permanent narrative, a concrete and unifying language, a powerful instrument of contrast to a tormented history made of political tensions that cannot be resolved, partly due to the enormity of the interests at stake and partly because humanism is the great loser of history, the great victim of utilitarianism as a moral theory.

Cyprus, therefore, is also a country where it is easy to land as a foreigner. English is widely spoken, certainly because of colonialism, but also because the young generations are losing the dialect of their grandparents, the one that was a little Turkish and a little Greek and a little neither, and the two language groups speak to each other in English. But even more than this, the Cypriots are naturally ready for the differences and the manipulation of the languages, which here are not the effect of some academic qualifications, but a primary need, the same as that Phoenician pepper merchant who saw his colleague loaded with lemons arriving from Sicily. One hundred languages are spoken and they are often spoken badly, mixing them in the same sentence, jumping from one to the other depending on the convenience, on the interlocutors, on the precision of the concepts, on the volume of the music. Each communication is easy and at the same time is a success, a natural conquest of the other.

It’s not all roses, of course. The historical division of the island carries its weight two, three times. The first time as a fact, because an island as large as Corsica cannot be divided in two: transport, currency, trade and social differences pay a very high and senseless price. The second time as a political tension, because on the North of the island the gloomy cloak of Erdoğan’s Islamist ambitions while the outcome of the Greek fascism of the Colonels carries its weight on the South, the one that in 1974 militarily deposed the only attempt to have a united government of the island by imposing the rhetoric «Cyprus is Greek», that means Christian, that means the enemy of the non-Christian — it does not matter if the Turkish Cypriots never go to the mosque, it does not matter if they are substantially atheists — and by triggering the Turkish military occupation, that is Islamist, and the division of the territory on an ethnic basis. The third time because Cypriots are unable to shake off the division as a fundamental element of their identity: in spite of the arts and the endless history, in spite of archaeology and a good ability to position themselves in the international context, any narrative about Cyprus seems unable to get rid of this premise, feeding it.

It is for this reason that I chose to move to Nicosia, the capital, the only important centre that is not on the coast, the divided city. Sleepy, non-touristy, yellow because of the sandstone, headquarter of universities, embassies, but eye of the UN storm, cooperation, refugee support NGOs, EU projects, hanging on the edge of the division like a sheet hanging out to dry, Europe on a side, Asia on the other. Not quite Europe and not quite Asia, however, just Cyprus, this is the Mediterranean, baby.

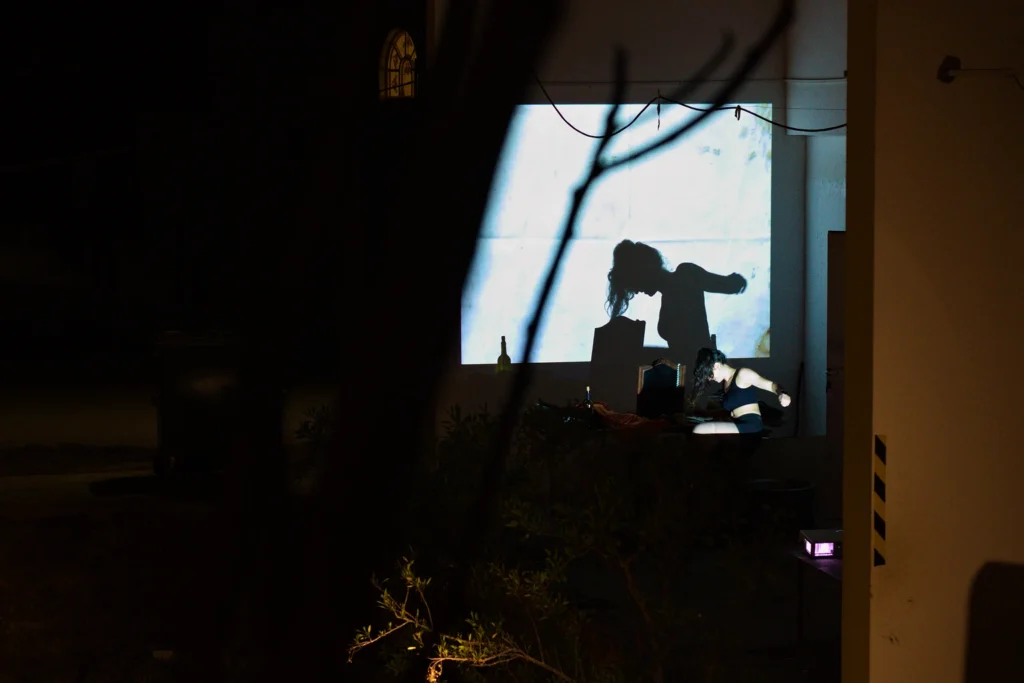

Nicosia is full of young people. Young, because the population is young, young because so many come for Erasmus or for cooperation, young because they are involved in politics, young because they do art, young because they do business, young because the young people talk to the elders, young because sex and love, young because they drink beer and wine and ζιβανία and rakı, young because they dance in a natural way, so natural that it seems they haven’t spent years training and studying.

Crossing the Ledra Street checkpoint, which keeps the same name on both sides, in the middle of the old city centre, gives a feeling of continuity and of a leap into hyperspace at the same time. Same faces, same ingredients, same fiery heat, same sand walls, same poor aesthetic, but a different language — and the same accent and the same English to permeate all conversations — different prices, different currency, the bells competing with muezzins for the air domain, the embargo, the McDonald’s that is there and can’t be here, the brand of beer that changes, the phone that jumps to another operator with different costs and, in times of virus, no dialogue between the two sides, only restrictions on crossing the checkpoints, despite the infection being so mild. Walking through the Buffer Zone from checkpoint to checkpoint — there are only nine on the whole island — barbed wire and ruins, the remnants of the division that is much more devastating than the war, because it splits a city: two independent aqueducts, two different migratory systems, two land management: rats and beetles do not undergo the same disinfestation. The Green Line is the veil that holds the two communities cheek to cheek and at the same time is a wall, impassable and militarized, crossed only by animals and by the techno music of the discos, hidden in the gardens or on the roofs.